The other day I was sitting at my desk upstairs typing away on my computer when I heard a strange tapping noise coming from below in the back garden. It persisted for some minutes and intrigued, I eventually got up and went downstairs to investigate. When I opened the front door and walked towards where the sound was coming from, a huge squawk resounded followed by a rapid flapping of wings as a cock pheasant took off and flew over the garden wall to the neighbour’s garden. Having heard such a disruptive, noisy take-off before, presumably made to startle a would-be predator, I was not too alarmed once I realised the nature of the creature producing it. I also soon realised what had been going on. In effect, said bird had seen itself reflected in the shiny surface of an old stainless steel clothes drier drum that my wife Nicola and I were using as a flower pot and thinking this refection was a rival, was attacking it for all its worth! How long it would have gone on doing this without my timely intervention I do not know, but one assumes it would have damaged its beak on the hard surface by continuing thus.

These pheasants are the survivors of the local winter shoot here on the edge of Exmoor in North Devon where Nicola and I live. They are bred especially for the occasion, and likely to hang out in gardens and away from the areas where the shooting takes place. I guess by a process of intense selection, the more intelligent birds eventually pass on their genes to the next generation, such that given enough time, a large percentage of the reared birds leave the immediate area and thus survive to fight another day…literally, certainly with fellow birds. We often see the male pheasants so engaged in such ritualistic battles with other males, either in the local fields or in the nearby lanes, where they are effectively oblivious to the dangers of people or other predatory creatures approaching, and especially to traffic, hence quite a few get run over in this way such that the local lanes and roads are littered with dead and dying birds, mainly, but not exclusively, cock birds. Hence the sex ratio may eventually become imbalanced as a consequence ‒ away from its normal 1:1 ratio.

The behaviour of attacking one’s reflected image, essentially because one doesn’t see this as self, is an interesting phenomenon for sure. I have seen this behaviour in a few other birds, usually males during the establishing of territories, both in robins and chaffinches seeing themselves in the wing mirrors of parked cars. Other local birds, such as jackdaws, of which we have a surfeit, seem not to engage in this reflection-bashing behaviour, perhaps because they are more intelligent and indeed can and do recognise self from non-self (as is known in Eurasian magpies, some reptiles, i.e. garter snakes, some fishes, i.e. cleaner wrasse, some crustaceans, i.e. Atlantic ghost crabs, as well as some ant species, according to Google). Youtube has recently shown a lot of different videos about the abilities of various animals, mostly mammals, to recognise self from non-self. Elephants apparently can as can chimpanzees and gorillas, but other animals such as bears and big cats can’t. Crucially, these latter animals, i.e. the ones that cannot determine self from non-self, are intelligent enough to find their prey and seek out mates and procreate and all. And presumably they can recognise their mates thereafter and the offspring so produced from a successful mating as their own, though doubtless scent comes into play in this respect. But they cannot recognise themselves!

So only some animals with suitable cognitive skills can recognise their own reflections as self, and other animals as non-self, possibly potential rivals. Elephants, dolphins and the great apes are highly social creatures, as are humans, but so are wolves and they can certainly identify other members of their packs, and the hierarchy within them, including ‘alpha males’ and ‘alpha females’ leading the pack, in reality the parents of the offspring comprising the pack.

Which brings me round to human facial recognition. As a molecular ecologist by profession it has always fascinated me how much genetic variation there is in terms of faces, and that members of the same family often bear striking resemblances to one another. Such resemblances can pass down family lineages for generations, suggesting that the genes coding for the key determining elements in shaping the skull are dominant. Interestingly, there are only relatively few key features in the design of the human face, including width and height, distance of the eyes from one another, shape of the nose and mouth, prominence of the chin, etc., something that AI-governed facial recognition systems utilise, as found at airports during checking of passports. Human beings find symmetrical faces the most attractive…apparently… because this suggests, presumably subliminally, that the person in question has good genes with few mutations leading to irregularities in facial architecture, as well as potentially other characteristics as well.

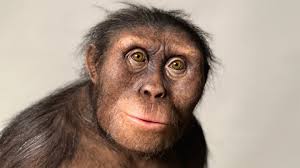

Presumably over time, perhaps going back millions of years to the period when our ancestors (e.g. Lucy) split from the true ape lineage and became human, without the advantages and glories (and failings) that we now see displayed, even to this day, then clearly recognising who was who was essential, as it still is, more especially friend from foe.

It humankind ever does succeed in cloning humans, as may well be possible, then it will be a strange and disturbing world indeed, with lots of multiple copies of people with the same face and features occupying the world. How will we then know friend from foe, pseudo-mother and -father from one’s true parents, pseudo-brother and -sister from true brother and sister, etc?

In this light, Nicola and I watched an interesting interview on Sky News the other evening in which the author and molecular biologist Adrian Woolfson was talking about the future potential and perils of AI and how one day, perhaps sooner than we realise, AI-guided robots, having understood the language of the genes and genome and how to read these completely (like understanding and writing one’s own native language or another foreign language), these will be able to create life, not only humans and existing life forms, but life forms that have never hitherto existed before on Earth during its 4.5 billion years of existence. And some of these creatures could be truly terrifying to behold and interact with.

To date, all living species have evolved by processes involving natural selection, à la Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. And it is amazing what evolution can do without a plan as such or forethought, just depending upon chance and necessity to drive the system forward. Evolution is not necessarily deterministic, although according to Google, can be when ‘leading to similar, optimal, or analogous phenotypes in similar environments’, i.e. convergent evolution. On the contrary, it is normally produced by random, stochastic events involving mutations of the genes, either positively or negatively selected over time. And if you don’t think that this is absolutely fantastic, which it surely is, please reflect on the existence of the stegosaurus, the brontosaurs and the tyrannosaurs, masterpieces of design and engineering brought about by natural section over millions of years. For example, even the Tyrannosaurs rex lasted about 3 million years, nearly as long as humans have been around…so far.

If such amazingly weird and scary creatures can be developed by random, largely non-deterministic processes, think what AI may be able to achieve once it has ‘sussed out’ how to read, and manipulate the genome, including the human genome?

Here I leave you with this thought. Knowledge is surely a good thing, but then again, as we well know, knowledge can be abused (and often is), and used to the detriment of humankind and other life forms. So perhaps we have to be very careful when we create systems that can manufacture and manipulate genes and genomes, something that is already happening to some extent with so-called designer babies and gene editing and modification and all (i.e. GMOs). But this is as nothing compared to what the future may ultimately bring in this direction. Something we should surely all reflect upon.

Hugh Loxdale

Cock Pheasant (Image ©Kent Wildlife Trust)

Lucy, belonging to the species Australopithecus africanus, a lineage possibly basal to the genus Homo, and which lived in southern Africa some 3.3 to 2.1 million years ago.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australopithecus_africanus

Image ©Science News Explores (https://www.snexplores.org/article/lucy-fossil-50-years-human-evolution)

Tyrannosaurus rex, which lived in western North America some 69 to 66 million years ago.

(Image ©New Scientist (https://www.newscientist.com/article/2511500-t-rex-took-40-years-to-become-fully-grown/)